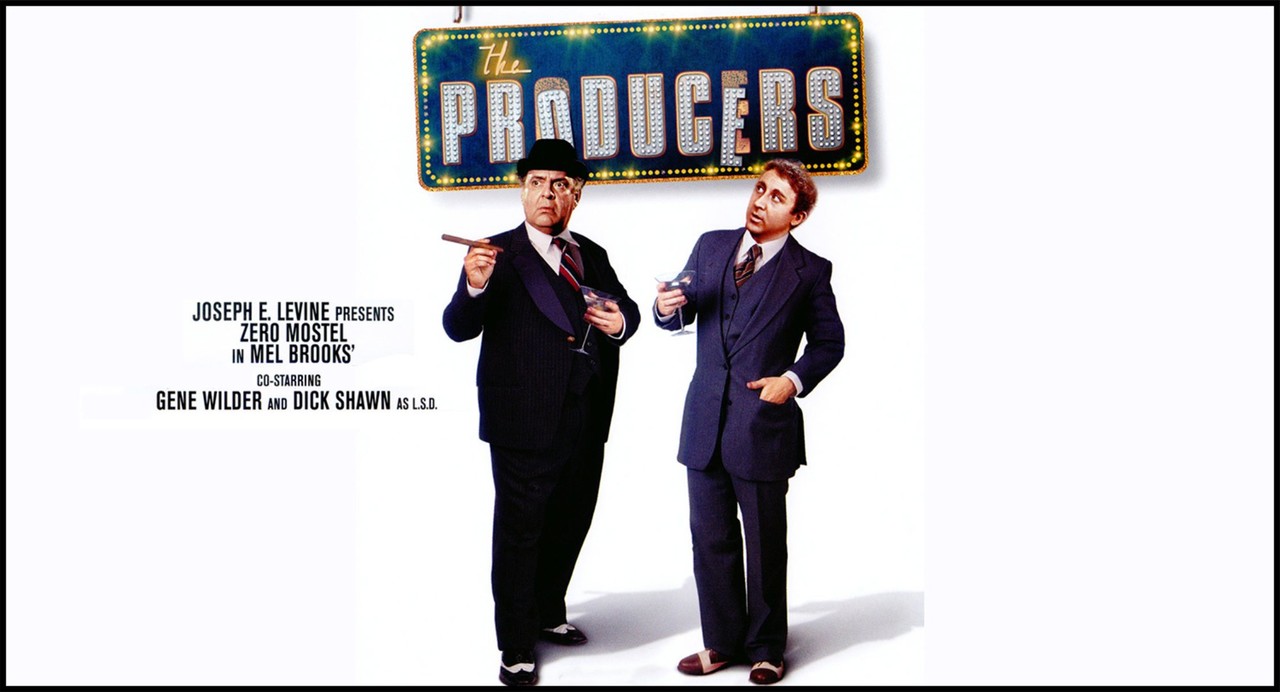

Lessons in Stock Picking from Hollywood: Mel Brooks, Gene Wilder, and the Theatre of the Absurd

The global box office generated over $38 billion dollars last year, up 5% on 2014’s total and 18% in the five years from 2011 to 2016.

Despite the success of the international film industry and outsized profits that are available to astute investors who are able to identify films that will resonate with viewers, industry estimates show that of any ten major theatrical films produced in a given year, on average, six to seven may be broadly characterised as unprofitable and one might break even.

However, for the 20% of films that make a profit the upside potential is huge. So far, this year’s best-selling movie release measured by total worldwide box office was Captain America: Civil War which generated over $1.5 billion in worldwide revenues on a budget of $250 million – achieving a 6x return on capital invested in just 77 days after its first release. Quite amazing!

For investors, however, big headlines and record-breaking ticket sales aren’t everything. Huge ticket sales are usually matched by huge production budgets, which means that despite these films bringing in a lot of money, they do not always provide investors with the best ROI. For instance, to date, James Cameron’s 2009 space epic Avatar has generated over $2.7 billion dollars in worldwide box office takings, making it the highest grossing movie of all time (incidentally, enough to fund NASA’s $2.5 billion Mars Exploration Rover Curiosity and explore space for real!).

Despite the film’s phenomenal success, it’s mammoth $425 million production budget meant it’s ROI was only just over 600% as compared to lower-budget action films such as Steven Spielberg’s 1975 classic Jaws with an ROI of over 1700% (generating almost $250 million on a paltry $12 million budget) or 2015’s supernatural horror film The Gallows (Heard of it? Me neither!) with an ROI of over 6700% (generating $6.5 million on a shoestring $100k production budget).

In fact, the top 20 movies with the best ROI’s is full of films of which you’d find hard to believe and indeed in many instances would never had heard of! But what makes a best-selling film? Which films offer the most lucrative risk-adjusted upside? Is it possible to predict big screen flops or successes? What characteristics, if any, do these films share and can they be used to make predictions for future success?

Given the many casual correlations between film and financial investing – i.e., the importance of hit rates, win/loss ratio, diversification, NPV analysis, critics reviews (sellside ratings?) and ROI’s – using a similar framework to that which is taught to and used by nearly all research analysts seems an obvious starting place.

To convey the full absurdity of treating the human drama of film (and stocks) exclusively by math’s, let’s construct here a similar mathematical theory for film investing using the same mathematical jargon and word format used by equity research analysts to value best-selling stocks.

The Film Asset Pricing Model (FAPM)

In silver screen investing, the Film Asset Pricing Model (FAPM) is a model used to determine a theoretically appropriate required rate of return of any movie in order to make decisions about whether a particular movie investment should be added to a well-diversified portfolio of film investments. The model takes into account a film’s genre or “Beta” to describe its sensitivity to the non-diversifiable movie industry as a whole.

Expected Film Return = Production Budget Bank Interest + Movie Genre (Film Industry Return – Production Budget Bank Interest)

The FAPM’s utility is very much linked to its simplicity – particularly in its assumptions - that all film investors are all knowing, emotionless robots whose sole aim is making profits in a world where taxes and costs do not exist! But in spite of this there are many problems with the FAPM, and not just academic or theoretical objections based on empirical tests.

Using the FAPM to gauge the real-world expected return of a film illustrates the practical issues of using such a basic, purely mathematical parse to predict film returns.

High profile “Bulge Bracket” movie research firms OpusData and Box Office Mojo conducted an extensive “empirical” study into the ROI’s of nearly 2000 films released between 2003 and 2012 that grossed at least $2 million domestically. Their research showed that the average movie earned 452% of its original production budget in global box office revenues, which to the financial analyst is equivalent to the market return over that period. The genre with the biggest box office ROI (or highest beta to the market) excluding documentaries was Horror. The average Box Office ROI of the 113 Horror films released over the period was 600% in purely American box office returns, and about 1200% in worldwide takings. Not such a scary investment after all!

Given this analysis, films in the horror genre would be expected to have a beta of around 2.65 (based on an average horror ROI of 1200% divided by the market average genre return of 452%). This however would provide very little comfort or assurances to any investors in the Quentin Tarantino/Robert Rodriguez Grindhouse double bill that grossed only $25 million theatrically from an overall production budget of $67 million – generating a negative ROI, a $42 million loss, and more than a few red faces of anyone whose “valuation model” predicted an $800 million profit using the FAPM.

The De Niro-Pacino Three Factor Model

The De Niro-Pacino Three Factor Model is a film pricing model that expands on the limitations of the Film Asset Pricing Model (FAPM) by adding size and value elements to the market risk factor in order to better explain the returns associated with movie investments. This model builds on the fact that smaller production budget films and films with better value “actors-for-the-buck” tend to deliver higher ROIs on regular basis. By including these two additional factors, the model is better able to explain and ultimately predict movie success.

Expected Film Return = FAPM + Small Budget Factor + Value Actor Factor

Despite a more robust valuation metric built on factors that prove significant across thousands of film returns, the De Niro-Pacino Three Factor Model would have still failed miserably to predict the box office turkey that was the Wachowski’s 2015 sci-fi adventure Jupiter Ascending.

The film took just $181 million dollars in worldwide box office receipts on a production budget of $179 million – only a $2 million profit on the face of it but in reality a significant flop given a film typically needs to generate an ROI of at least 350% over its production budget to break even when taking into account advertising and distributor fees.

It would have been nearly impossible for any film investor to have predicted the films failure based exclusively on mathematical formulae deduced from the millions of historical film metrics and data points – let alone the De Niro-Pacino model!

Jupiter Ascending would have scored highly on the Small Budget Factor given it’s relatively modest $179 million budget was low relative to that year’s big production movies such as Avengers: Age of Ultron, Spectre, and Star Wars: The Force Awakens which cost $279 million, $245 million, and $200 million respectively.

The film would have scored equally highly on actor value, with stars such as Mila Kunis, Channing Tatum, Eddie Redmayne, and Sean Bean among those that have been voted the best value-for-the-buck actors in recent years based on the ratio of their salary-to-box-office takings.

We could always try to extend or improve the De-Niro-Pacino film pricing model by adding additional factors – such as momentum. Such a model could perhaps be named the Shawshank 4 factor model after the films initial box office flop became profitable following months of positive momentum gains in the video rental and TV licensing markets.

In reality, there were many warning signs for the shrewd investor who was willing to look in the right places. The Wachowski’s closest ally and president of Warner Bros Jeff Robinov who greenlighted the project left the studio while the picture was still in its development stages (key man risk?), which caused the project to overrun its initial $130 million budget (risk management?), with the directors themselves refusing to fund the gap as they had done previously with Cloud Atlas (lack of confidence?). In addition, according to insiders the film had tested poorly in early screenings which later caused the studio to delay the launch date in order to fix the issues which in aggregate proved clear red flags predicting the inevitable failure of the film, despite all the “hard data” that pointed to the contrary.

There are clearly limits to the extent to which mathematics can be used to explain films or businesses whose successes and failures are based on human, subtle and often more logical factors. There are hidden qualities inherent in both films and stocks which cannot be captured by equations, such as the characters of the script, the quality of the conflict, or the writing ability – just as financial mathematics cannot capture the character of management teams, the quality of businesses, or management’s execution ability.

“We got the wrong play, the wrong director, the wrong cast. Where did we go right?"

Max Bialystock (The Producers)